Geology of the Table Rocks

Southwest Oregon has a rich, diverse, and complex geologic history. Geologic features in the region range from the ancient Klamath-Siskiyou Mountains to the geologically young High Cascade Mountains. The flat-topped mesas of the Table Rocks, with their own unique geologic history, provide a look into the forces that shaped and continue to shape southwest Oregon.

Rising dramatically 800 feet above the valley, these iconic landforms are named according to their relationship along the Rogue River. Upper Table Rocks being up stream of Lower Table rock. They are approximately 2000 feet above sea level.

Let’s take a walk back in time and find out how the Table Rocks were formed.

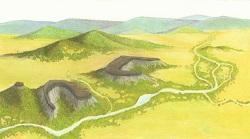

If you decide to embark on a hike to the summit of Table Rocks you will observe two distinct rock types on your trip. The lower 700 feet forms the sloped, softer sedimentary rocks of the Payne Cliff Formation and upper 100 to 200 feet is the vertical andesite lava cap.

The sedimentary rocks of the Payne Cliffs Formation were formed by rivers and streams that deposited over 1,000 feet of sandstones, conglomerates and mudstones, during the Eocene Epoch (48 to 34 million years ago). The climate was tropical to subtropical during this time period. The Payne Cliffs Formation had different source rocks throughout time, with the greatest source being the Klamath Mountains.

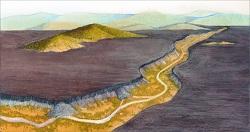

About seven million years ago a large shield volcano, perhaps near present day Olsen Mountain, erupted the andesite lava of Table Rock. This lava flow was approximately forty-four miles long and spread out over the entire valley. Outcrops of the lava flow can be found from east of Prospect to Sams Valley. The maximum know thickness of the andesite flow is 730 feet, near Lost Creek Lake.

By Shady Cove the lava flow is over 400 feet thick. In the area of Table Rocks, the flow was 100 to 200 feet thick and covered the Payne Cliff Formation.

The lava filled the ancient Rogue River, its tributaries and the surrounding valley. Evidence of the lava being in contact with water can be seen at Upper Table Rock. In some places, the bottom six feet of the lava is porous and soft. This is because when the molten lava flowed on top of the water, the water was instantly turned to steam creating a scoriaceous texture or small holes in the rock.

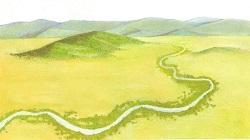

Over the following millions of years, the ancient Rogue River meandered back and forth across the valley, eroding or carving away most of the sheet of lava and the underlying softer Payne Cliff Formation.

The power of the river can be appreciated when you realize that seven million years ago, the entire valley was about 700 feet higher than it is to day. For unknown reasons, the forces of nature left the Table Rocks behind when most of the remaining valley was carried off to the ocean.

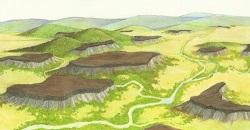

The andesite of Table Rocks is a gray to black, glassy rock. As the flow cooled, it contracted to produce the distinct pattern of columnar jointing. These cracks are the result of the lava flow shrinking while it was cooling down. They frequently form a hexagonal pattern and are perpendicular to the direction of the flow. You can witness columnar jointing by looking at the large monoliths as you hike the trail.

Erosion is still an active force and can be seen in the many monoliths and talus slopes as you near the tops of the rocks. Who knows, in another 7 million years, perhaps they’ll be gone too!