Takelma Culture

How Were Baskets Used by the Takelma?

of Aleena Turpin

The Takelma collected many basket-making materials in the spring and summer, but focused on basket-making during the winter. Some materials used for Takelma basketry included hazel shoots, maidenhair-fern stems, willow shoots, bear grass, pine roots, porcupine quills, and iris leaves. Baskets were used for cooking, transportation of goods, and storage. They came in all shapes and sizes, from large storage baskets, to small plates and cups, and even the artistically woven caps. Baby cradles were made of large baskets, tightly woven and lined on the inside with rabbit fur. Tightly woven baskets were used for cooking because they were watertight. The Takelma filled them with water, added hot rocks from the fire, and boiled numerous plant and animal foods (Gray 1987).

Basketry Materials

- Bear Grass: Actually a type of lily, this is an importation plant for basketry material

- Iris: leaves used in basket making

- Porcupine quills: Used for decoration on baskets

- Maidenhair fern: black stem used for decoration on baskets and hats

How did the Takelma prepare Acorns?

Large quantities of acorns were collected in the late summer and early fall. After the acorns were collected, they were dried and could then be kept for years, if the supply lasted. Many people prefer aged acorns over fresh ones (Kentta 2004). To prepare acorns, they are shelled and cleaned. They are then pounded with a stone and ground into a fine meal or flour. This acorn meal was then placed into a carefully formed basin made from basketry or in the sand, and then rinsed thoroughly and repeatedly with cold water to leach out the bitter flavor or the tannins (Kentta 2004). The flour or meal was combined with water in a water-tight basket. Hot rocks from the fire were added to cook the mush or porridge. The finished product was used in several different ways including eaten like a hot cereal or formed into breads and cakes. Dried manzanita berries were often used to add flavor to both the cakes and porridge (Sapir 1907b: 257-58).

How Did the Takelma Prepare Camas?

The Camas bulbs were removed from the ground with a digging stick made from birch-leafed mahogany, fitted with a cross piece handle of carved deer or elk antler. Camas bulbs were sometimes gathered in the spring to avoid confusion with death camas, but nutrient levels were much higher in the late summer/fall, so many bulbs were collected then as well. The collected bulbs were placed in an "earth oven," a pit three to four feet deep dug into the ground with a layer of hot rocks and greens and bark on top. Once properly layered, the pit was covered with earth and the bulbs left to bake for 24 to 48 hours. Based on the length of time the bulbs were baked, they came out soft, sweet, and syrupy and ready to be eaten directly or hard, dried, and ready to be ground into flour. The flour was reheated later to make into porridge or used to make bread-like foods during the winter (Sapir 1907b: 258).

What tools did the Takelma use?

The tools used by the Takelma consisted of implements made of stone, bone, antler, and wood, as well as woven materials. The stone tools included projectile points (arrowheads) and other small flaked-stone tools made from obsidian, jasper, agate, and even petrified wood. Rock slabs were used to pound acorns and other materials. Numerous other tools including pestles and mortars, hammerstones, and stone pipes were made from stone. Tools made from bone and antler included harpoons (for fishing), needles, spoons, scratching sticks, and elkhorn wedges. Deer or elk sinew and pitch from trees were used for attaching tool pieces together, and sinew or iris fiber twine was used as thread. Implements made from wood included bows, arrows, needles, atlatls, spoons, digging sticks, and stirring paddles. Roots, grasses, and bark were woven to make baskets, cups, plates, cradles, trays, and hats (Satler 1979).

Hunting large game

Takelma used several techniques to hunt deer. They wore a deer head disguise to stalk and get close enough to the deer to spear them with an atlatl or use a bow. Dogs and fire were used to corral deer into an enclosure. The trapped deer were then killed with clubs (Gray 1987:33). Elk were too powerful to be snared easily so herds were driven into passes or ravines where hunters waited to kill them. Traps and pits were also used to capture elk and deer (Pullen 1995:IV-6).

Ceremonies and spiritual beliefs of the Takelma

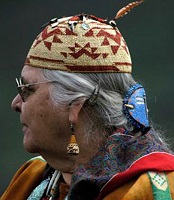

Agnes Baker-Pilgrim

The Takelma expressed many spiritual beliefs through their myths and legends and the mythological characters found in these stories—several of which relate to the Table Rocks area. This belief system is described as animistic and is based on the belief that all natural objects are inhabited by a spirit. Animists also believe humans possess souls with a distinct life that is separate from the human body before and after death. Anthropologists consider animism to be probably the oldest form of religious belief on earth.

For the Takelma, the spirits were associated with particular plants, animals, and places thought to be the transformed manifestations of primeval earthly inhabitants (Gray 1987:43, Sapir 1907a:34). Animals, plants, rocks, and weather all had spiritual meaning and a person's fate, as well as events of nature, were controlled by supernatural spirits. Thus, although maintaining good relationships among and between people was important, it was also crucial for the Takelma to maintain positive interactions with the many unseen spirits (the plants, the trees, the rocks, the animals) that surrounded them (Tveskov 2002:15).

Mediation between the spirit world and the Takelma was normally accomplished by a shaman (Goyo). A shaman obtained their special powers from one or several guardian spirits, which were contacted during fasting and praying in the mountains (Sapir 1907a:41). A shaman held extraordinary powers to effect good or evil. Ceremonies were also a part of Takelma life, though they were limited to the practice of certain rituals during important crises and life phases, during warfare, and for annual renewals of significant food resources (Gray 1987:40, Sapir 1907a). Annual renewal ceremonies focused on the two main food resources of the Takelma, the acorn and the salmon. Their First Salmon ceremony was probably very similar to those practiced by other Native groups in the Pacific Northwest. The object of the ceremonies was to ensure the return of large populations of spawning salmon and abundant acorn crops (Sapir 1907a:33).

A version of these subsistence ceremonies has been revitalized today in the Rogue Valley. The eldest surviving Takelma elder, Agnes Baker-Pilgrim, is an active member of the local Native community. Though a huge amount of traditional Takelma culture was lost, Agnes has made an effort to learn as much as possible about her people and their history. Agnes has restarted the tradition of both a salmon and an acorn ceremony in the hopes of further sharing her knowledge about Takelma culture with other Native descendants and the general public. All are encouraged to attend these ceremonies which take place in the summer and the fall!

- References

-

Aiken, Melvin C.

- 1990 Southwest Oregon: Living With the Land. In Living With the Land: The Indians of Southwest Oregon. Nan Hannon and Richard K. Olmo, eds. Pp. 1-5. Medford, Oregon: Southern Oregon Historical Society.

Atwood, Kay

- 1994-95 As Long as the World Goes On: The Table Rocks and the Takelma. Oregon Historical Quarterly 95(4): 516-532.

Beckham, Stephen Dow

- 1993 Takelman and Athpascan Lifeways and History, Rogue River Corridor-Applegate River to Grave Creek: Investigations for Interpretive Programs. Eugene, Oregon: DOI Bureau of Land Management, Medford District Office.

Gray, Dennis J.

- 2003 Flounce Around Fuels Cultural Resource Inventory. Medford, Oregon: U.S.D.I. Bureau of Land Management.

- 1993 Analysis of the Fish Lake Artifact Collection, Site 35JA163, Jackson County, Oregon. Medford, Oregon: U.S.D.I. Bureau of Land Management.

- 1987 The Takelma and their Athapascan Neighbors: A New Ethnographic Synthesis for the Upper Rogue River Area of Southwestern Oregon. Eugene, Oregon: University of Oregon Anthropological Papers No. 37.

Kentta, Robert

- 2004 website edits. Cultural Resource Director for Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians.

LaLande, Jeff

- 1991 The Indians of Southwestern Oregon: an Ethnohistorical Review Anthropology Northwest: Number 6. Dept. of Anthropology - Oregon State University, Corvallis.

- 2004 So, Just How Extensive was Anthropogenic Fire in the Pacific Northwest?: Southwestern Oregon as a Case Study. Eugene, OR. Paper presented at the Northwest Anthropological Conference.

LaLande, Jeff and Reg Pullen

- 1999 Burning for a ‘Fine and Beautiful Open Country’: Native Uses of Fire in Southwestern Oregon. In: Robert Boyd (ed.), Indians, Fire, and the Land in the Pacific Northwest. Oregon State University Press, Corvallis.

Pullen, Reg

- 1996 Overview of the Environment of Native Inhabitants of Southwestern Oregon, Late prehistoric Era. Medford, Oregon: DOI Bureau of Land Management, Medford District Office.

Sapir, Edward

- 1907a Religious Ideas of the Takelma Indians of Southwestern Oregon. Journal of American Folk-Lore 20:33-49.

- 1907b Notes on the Takelma Indians of Southwestern Oregon. American Anthropologist 9(2): 51-275.

Satler, Timothy

- 1979 Preliminary Report of Test Excavations at Salt Creek Site in Southwestern Oregon. Medford, OR: DOI Bureau of Land Management, Medford District Office.

Tveskov, Mark, Nicole Norris, and Amy Sobiech

- 2002 The Windom Site: A Persistent Place in the Western Cascades of Southwest Oregon. Ashland, Oregon: SOULA Research Report 2002-1.