You are viewing ARCHIVED content published online before January 20, 2025. Please note that this content is NOT UPDATED, and links may not work. Additionally, any previously issued diversity, equity, inclusion or gender-related guidance on this webpage should be considered rescinded. For current information, visit https://www.blm.gov/blog.

Lode & Placer: 150 years of mining claims on public lands

by Heather Feeney, Public Affairs Specialist

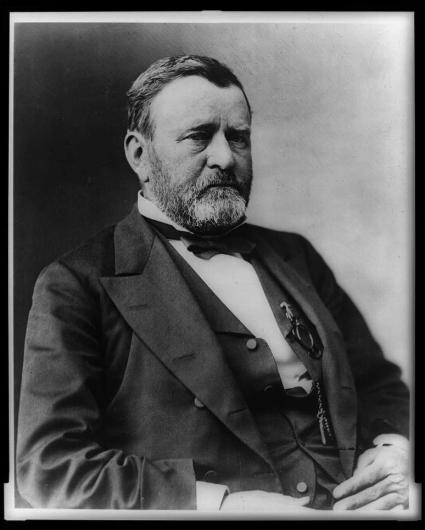

On May 10, 1872, President Ulysses Grant signed An Act to promote the Development of the mining Resources of the United States, which Congress had passed the previous month. It declared "all valuable mineral deposits in lands belonging to the United States ... free and open to exploration and purchase ... by citizens of the United States and those who have declared their intention to become such ... ."

Ten weeks earlier, Grant had signed AN ACT to set apart a certain tract of land lying near the headwaters of the Yellowstone River as a public park, the Yellowstone National Park Protection Act, creating the world's first national park "for the benefit and enjoyment of the people."

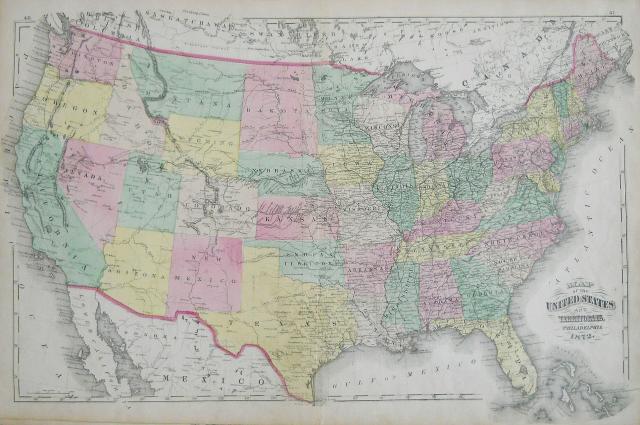

The later, perhaps less celebrated law is known as the General Mining Law of 1872, and it continues to govern development of hardrock minerals on federal lands. It had combined two earlier laws dating from 1866 and 1870, and established a means to patent, or take full title to, federal lands where a mineral claim has been located, or staked. While the 10-year-old Homestead Act had established a pathway for settling the West with family farms, the new Mining Law promoted settlement by bringing commerce and finance to frontier areas that were less suitable for agriculture.

The General Mining Law initially covered all types of minerals found on federal public lands. Staking a claim made the minerals found on that claim locatable and made them the property of the claimholder, who could also file for title to the land, if they wished.

This represented the entirety of U.S. mining law for nearly 50 years, until the Mineral Leasing Act (1920) deemed fluid minerals such as oil and natural gas, along with coal, phosphates, potassium and sodium, leaseable - meaning these minerals and the lands where they were found remained the property of the United States. Following World War II, the Mineral Materials Act (1947) established still another category of materials like sand, gravel, stone and pumice, which were deemed saleable and made available through their own process, which also does not include the opportunity to acquire title to the lands.

As the post-War economy grew, some mineral resources came to be seen as especially important for national security. The U.S. Geological Survey periodically publishes a list of non-fuel minerals and mineral materials that are essential to the economic or national security of the United States and which have a supply chain vulnerable to disruption. Nearly all of these critical minerals are locatable and so are mined under terms of the General Law if found on federal lands. Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland recently announced a review of how the U.S. regulates and permits domestic production of critical minerals.

Language in the Yellowstone park act withdraws "from settlement, occupancy, or sale under the laws of the United States" the lands it sets apart as a public park "under the exclusive control of the Secretary of the Interior." The Secretary and Congress have authority to withdraw public lands from location and entry under the 1872 Mining Law to maintain other public values in a specified area or to reserve the area for another particular public purpose or program. Withdrawals do not extinguish valid rights that pre-date the withdrawal order or statute. They preclude new claims on the specified lands.

This year (2022) is the bicentennial of Ulysses S. Grant's birth, on April 27, 1822, in Point Pleasant, Ohio.

Thomas Moran completed his iconic painting "The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone" just as the Protection Act was being passed. The monumental canvas is exhibited at the Interior Museum, which recently re-opened to in-person visits, in the Stewart Lee Udall Department of the Interior Building, 1849 C Street, NW in Washington, DC.

Heather Feeney, Public Affairs Specialist

Related Stories

- A former boomtown’s second life as storyteller in New Mexico

- National Conservation Lands: 25 years – and eons – in the making

- BLM publishes interactive web map displaying access to public lands

- BLM announces 2025 fee-free days

- Fourth Restoration Landscape film highlights Cosumnes Watershed fire and fuels reduction efforts