You are viewing ARCHIVED content published online before January 20, 2025. Please note that this content is NOT UPDATED, and links may not work. Additionally, any previously issued diversity, equity, inclusion or gender-related guidance on this webpage should be considered rescinded. For current information, visit https://www.blm.gov/blog.

Easing trauma with public lands and resources

June is Post Traumatic Stress Disorder Awareness Month. A person who has difficulty recovering after experiencing or witnessing a terrifying event can develop PTSD, a serious and sometimes debilitating mental health condition. Symptoms can include nightmares, unwanted memories, avoidance of certain situations, heightened reactions, anxiety, or depression. It can last months or years and triggers can cause flashbacks accompanied by intense emotional and physical reactions. Medical intervention, including psychotherapy and medications, are often warranted.

Law enforcement officers, military Veterans, first responders, and others in high-stress occupations experience higher rates of PTSD as these jobs are more likely to cross paths with trauma. According to the National Center for PTSD, a program of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, about six out of 100 adults will experience PTSD at some point in their lives. By contrast, about 23 out of every 100 veterans using the VA Healthcare System experience PTSD at some point. This rate may be even higher when veterans using private care—or seeking no care—are considered.

In the case of BLM law enforcement, an added stressor comes from the fact that officers often work alone in remote areas where backup is hours away.

The Law Enforcement Mental Health and Wellness Act of 2017 recognizes that law enforcement agencies need and deserve support to protect their employees’ mental health and wellbeing. Executive Order 14074 requires those agencies to develop their own wellness practices and policies for Federal officers.

Andrew Prys, Senior Special Agent, is on a detail to do just that as the BLM Law Enforcement Wellness Coordinator in the Office of Law Enforcement and Security. With nearly two decades in law enforcement and partnering with the National Interagency Fire Center, other DOI agencies, and the U.S. Forest Service, he’s developing the BLM Law Enforcement Wellness Program. Goals include reducing cultural stigma within the law enforcement community against getting help and strengthening protections against stressors, trauma, and poor health outcomes.

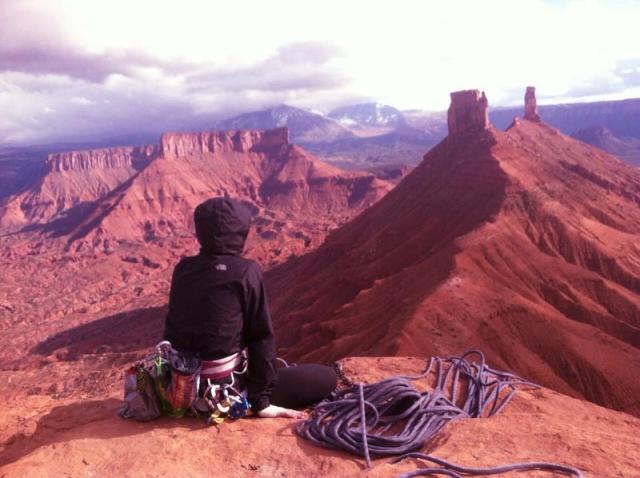

The program integrates BLM law enforcement officers’ physical, emotional, mental, and spiritual health; it includes improvements in hiring, retention, diversity, and inclusion. The theme is connectivity–connecting to nature and connecting to each other.

“Even if we’re alone in nature, we’re not alone,” said Andrew. “Nature is a great listener and teacher. When I return from mountain climbing, I’m better for it. I show up better for the community.”

While nature is a great healer, sometimes something stronger is needed. Andrew explains that BLM active and retired law enforcement officers and their families have access to Cordico, a wellness app that provides access to licensed clinicians, peer supports, chaplains, and fitness incentives. It features videos and self-assessments for stress reduction, sleep improvement, suicide prevention, financial education, better nutrition, and more. Healthy officers have effective interactions with the public, which in turn positively affects their view of BLM law enforcement.

BLM employees, regardless of their job title, also have access to a free health and wellness app, called Headspace. This app allows users to explore guided mindfulness activities and events, including getting better sleep, quieting your mind, being present, or managing stress and anxiety. To learn more about it, enroll in the virtual Headspace training through the National Training Center.

Military Veterans, like law enforcement officers, not only are more likely than civilians to have PTSD, but their suicide rate is 1.5 times higher. BraveHearts understands this more than most and uses horses to help veterans connect with their emotions. As Winston Churchill once said, “no hour of life is lost that is spent in the saddle.”

Since 2007, BraveHearts has been nationally recognized for providing equine-assisted services to Veterans across the country, but primarily in Illinois and Wisconsin. They are the largest equine-assisted services program for Veterans in the country, serving more than 1,000 Veterans in the last year.

Imagine spending years away from home, in one unfamiliar location or many, surrounded by people who would sacrifice their lives for you as much as you’d sacrifice yours to protect them. All the while you spend your time in this tight-knit community with your days and your tasks highly structured, following a clear command structure. Then imagine you’re back home with few or no support structures, surrounded by people who may have difficulty relating to that world.

Now imagine a Veteran, almost giving up hope of ever feeling normal again, finding commonality with a mustang. Both are intelligent, independent, hypervigilant, slow to trust, wary, loyal, and strong. Meggan Hill-McQueeney, President and Chief Operating Officer of BraveHearts, adopted four horses from BLM in 2013 to teach Veterans how to gentle the wild mustangs. Four years later, these mustangs, who began their lives on BLM land, participated in the Trail to Zero ride in New York City. Trail to Zero is a 20-mile ride on horseback through major cities to bring attention to Veterans’ high suicide rate and the benefits of using equine-assisted services for healing.

Last year Laura Steiglitz, former U.S. Navy Corpsman, rode her favorite mustang, Oatie, in the Trail to Zero ride in New York City, carrying the ribbons of six veterans who died by suicide.

“Oatie and I really helped each other. When I felt overwhelmed and overstimulated, he helped ground and calm me, and I did the same for him,” she said. “Mustangs and Veterans – we’re both hypervigilant, so when I see my horse standing calm, it reminds me there’s no immediate danger, so I can relax and breathe.”

Laura’s confidence carries beyond the ranch as she learns how to use her gifts to best help others, including demonstrating the benefits of working with mustangs to a group of Mounted Police Officers.

BraveHearts is training their third group of mustangs and is now mentoring five other centers on using mustangs to work with Veterans. They only work with centers that are accredited through the Professional Association of Therapeutic Horsemanship International (PATH Int.).

“What works best for our program is we pace ourselves by the mustang’s time and the Veteran’s time, rather than rushing our efforts based on others’ expectations.” said Meggan. “Slow and safe.”

Connectivity. Community. Mindfulness. Slow and safe. Useful regardless of your profession—military or civilian, law enforcement or fire, and whether you’ve experienced trauma or simply the challenges of everyday life.

Cathy Humphrey, Experienced Services Program

Related Content

Related Links:

- Law Enforcement Mental Health and Wellness (LEMHWA) Program Resources

- BraveHearts – the largest healing horsemanship program in the nation for Veterans

- Trail to Zero ride to end Veteran suicide

Related Stories

- Overcoming challenges to move the BLM forward: Nikki Haskett

- BLM recreation sites available to all: Exploring accessibility on Arizona’s public lands

- Connecting Utah students to public lands careers

- A day in the life of a BLM Hobbs Petroleum Engineering Technician

- BLM Recreation Sites Available to All: Exploring Accessibility on Alaska’s Public Lands