You are viewing ARCHIVED content published online before January 20, 2025. Please note that this content is NOT UPDATED, and links may not work. Additionally, any previously issued diversity, equity, inclusion or gender-related guidance on this webpage should be considered rescinded. For current information, visit https://www.blm.gov/blog.

Challenge & Opportunity: 1952 and 2022

by Heather Feeney, BLM Public Affairs

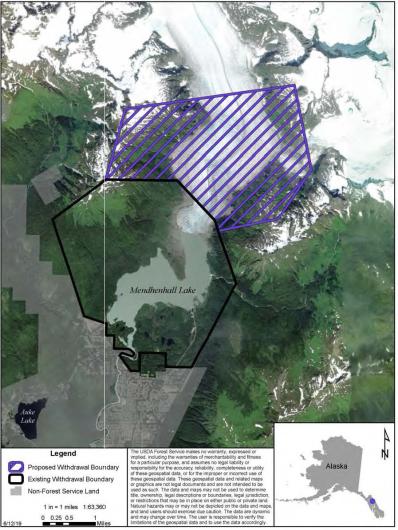

UPDATE: This story originally ran in January 2022, as the BLM began evaluating the withdrawal of additional public lands at the Mendenhall Glacier. Public Land Order No. 7922 was signed on June 2, 2023, withdrawing 4,560 acres to maintain the natural setting and protect recreational and natural resource values.

Glacial change

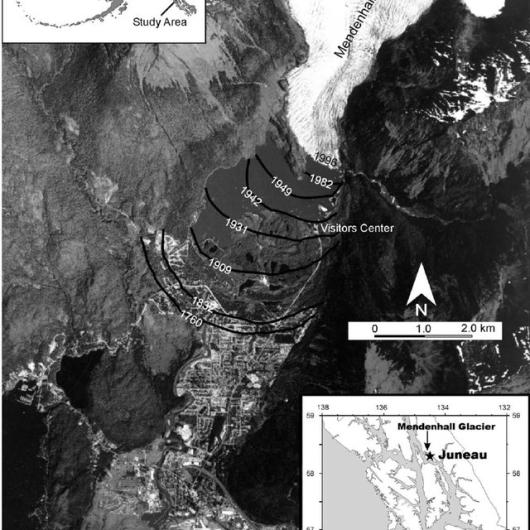

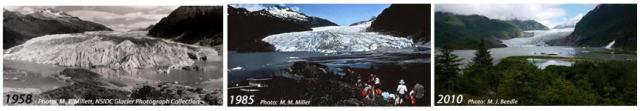

Each year, some 700,000 people visit Alaska’s Mendenhall Glacier on the Tongass National Forest. Its location – just 12 miles from downtown Juneau – makes it one of the most accessible glaciers in the U.S., a place to safely view and experience a unique aspect of the natural world. But even as more and more visitors seek to glimpse the ice, it has been steadily receding from view. Since the 1750s snowfall at the site has been less than the rate of melting. By 2050 the glacier is expected to be completely out of view from the U.S. Forest Service Visitor Center at the southeast corner of Mendenhall Lake.

To the Forest Service, this is a challenge for managing visitor and recreation services: how to keep the glacier accessible to people who want to experience it – whether that’s viewing it and capturing a memory through a lens or engaging more actively with the landscape by hiking a trail or paddling the lake.

The Bureau of Land Management has a role behind the scenes in preserving the integrity of the scenic values at Mendenhall and the quality of the experiences available to visitors. The agency administers rights to mineral leasing, entry and development on federal public lands, including those on the National Forest System. The lands being uncovered as the glacier recedes are unprotected from potential claims under mining laws, which could have adverse effects on the visitor experience at Mendenhall.

The two agencies are cooperating in an action called withdrawal to protect the scenic values and related experiences for current and future generations of visitors.

The flow of history

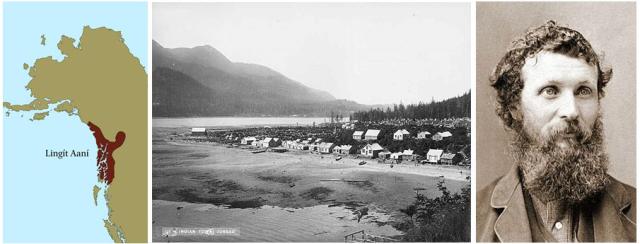

Mendenhall Lake and Glacier are part of ancestral lands of the Tlingkit (Lingít Aaní), who knew the area as Sitaantaagu. The Aak'w Kwaan band lived in the valley, and American naturalist John Muir adapted their name to christen the glacier “Auke” in journals of his visit in 1879.

The geographic name was changed in 1892 to honor Thomas Corwin Mendenhall, Superintendent of the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey, now part of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Under Mendenhall’s administration the Survey completed work to finalize the international border of southeast Alaska and settle a boundary question the U.S. had inherited when it purchased Alaska from Russia in 1867.

The geologic record shows that before 1750 the Mendenhall Glacier was advancing, but as the Little Ice Age came to a close, it then began slowly retreating. The ice and the lake, which formed in the early 1900s from meltwater, became part of the Tongass National Forest when President Theodore Roosevelt established it in 1907. They became a matter for the Department of the Interior following World War II, when the USFS Regional Forester established the Mendenhall Glacier Recreation Area (1947).

The Forest Service’s classification of the glacier, lake and surrounding acres as an area for public recreational use immediately excluded “all occupancy and use inconsistent with Recreation Use,” but it could not make the lands ineligible for entry and location under U.S. mining laws, to preclude claims and subsequent development of mineral resources. Only the Secretary of the Interior – with delegated presidential authority – could withdraw lands from such eligibility.

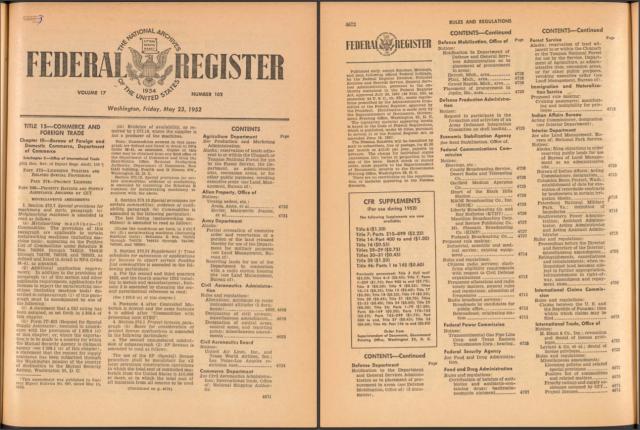

On May 16, 1952, Secretary of the Interior Oscar L. Chapman signed Public Land Order 829, withdrawing “from all forms of appropriation under public land laws” 5,815 acres of Federal public land classified as the Recreation Area, removing these lands – subject to valid existing rights – from eligibility for mining claims under the General Mining Law of 1872.

Ten years later, the Forest Service opened the Mendenhall Glacier Interpretive Visitor Center, the first of its kind in the National Forest System and originally designed to accommodate 23,000 people per year.

But even as renovation and enlargement of the visitor center (1997-99) later increased its capacity to 485,000, the glacier continued retreating, exposing lands that are not formally withdrawn under PLO 829 to mineral prospecting.

Paper trails

Federal land managers have determined the need to act again to protect scenic and recreational resources in the Mendenhall Valley, and withdrawal by Public Land Order is once again at the heart of the effort. The BLM and USFS are now working to withdraw 4,560 acres adjacent to the original withdrawn lands to preclude any development that would impact the resources visitors experience at what is now called the Mendenhall Glacier Recreation Area.

Withdrawal in 2022 proceeds differently than in 1952. The Mining Law of 1872 still governs mineral entry and location, the acres now proposed for withdrawal remain part of the Tongass National Forest, and withdrawals of federal lands from mineral entry and location are still accomplished by Public Land Orders. Today, however, there are several additional steps before the Secretary can sign an Order.

Among the many provisions of the Federal Land Policy and Management Act (FLPMA; 1976) is reform of the process that produced PLO 829. Withdrawal authority had been delegated to the Secretary of the Interior by a series of presidential Executive Orders in the 1940s. The President’s authority derived from the General Withdrawal Act of 1910, commonly known as the Pickett Act. FLPMA repealed Pickett, along with parts of 28 other laws related to withdrawal authority to create a more orderly and accountable process.

Section 204 of FLPMA and the regulations and policies that give it force in the BLM’s everyday operations are now part of considering any proposed withdrawal. Lands can no longer be withdrawn in perpetuity, and existing withdrawals are subject to periodic review to ensure that they are still serving their intended purpose. Those accomplished under FLPMA have an effective term noted in the PLO, after which they automatically terminate unless extended. The Forest Service has asked for a term of 20 years on the new Mendenhall withdrawal, with the possibility of requesting renewal once the initial term expires.

FLPMA also brings principles of public involvement and environmental review and conservation to the BLM mission. Passage of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) in 1969 had established these principles to inform federal decisionmaking, and FLPMA stated Congress’ intent for these to be a part of the BLM’s work – including consideration of withdrawal applications. For this reason, the Bureau has taken public comment on the new withdrawal application, and the Forest Service is preparing an environmental assessment of the proposed withdrawal. This input will inform the Secretary of the Interior’s ultimate decision on the current withdrawal application.

Places to find unity and forge common bonds

In support of President Biden’s America the Beautiful initiative, the Secretaries of Agriculture, Commerce, and the Interior, and the Chair of the Council on Environmental Quality have issued a preliminary report on conserving 30 percent of U.S. lands and waters by 2030. They identify three threats to these resources and their ability to sustain and support the nation, local communities, families and personal well-being: the disappearance of nature, the impacts of climate change, and lack of access to the outdoors. The report also recognizes the foundational importance of natural resources to America’s economy and the crucial need to listen, learn and provide support for conservation efforts of all kinds.

The current effort to protect the unique resources at “the Glacier behind the Town” and keep them safely accessible to visitors, who are a significant part of the economy of southeast Alaska, gives place to these issues. The Forest Service’s vision for the Mendenhall Glacier Recreation Area aims to match increasing demand and changing landscapes with updated infrastructure.

Managing the Secretary’s consideration of the withdrawal request lends the BLM’s continuing support to cooperation at all levels to meet the challenge of ‘giving every person in America – present and future – the chance to experience the freedoms, joys, bounties and opportunities that the nation’s lands and waters provide.’

Heather Feeney, BLM Public Affairs

Related Stories

- Exploring the Campbell Tract Special Recreation Management Area: Flora, fauna, and volunteer opportunities

- BLM Colorado, Grand Junction Field Office host recreation summit

- National Conservation Lands: 25 years – and eons – in the making

- BLM publishes interactive web map displaying access to public lands

- BLM announces 2025 fee-free days