You are viewing ARCHIVED content published online before January 20, 2025. Please note that this content is NOT UPDATED, and links may not work. Additionally, any previously issued diversity, equity, inclusion or gender-related guidance on this webpage should be considered rescinded. For current information, visit https://www.blm.gov/blog.

Celebrating an enduring resource and an unfiltered view of nature

By Derrick Henry, Public Affairs Specialist

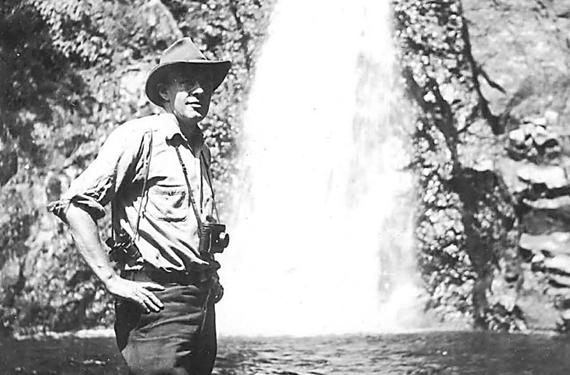

In 1956, a conservationist wrote the initial draft of legislation that would have Congress designate wilderness areas. The author died four months before the bill became law. His name was Howard Zahniser. The law, signed September 3, 1964, was the Wilderness Act, an enactment synonymous with this month’s celebration.

During National Wilderness Month, we encourage everyone to experience our Nation’s outdoor heritage, to recreate responsibly and to leave no trace, to celebrate the value of preserving an enduring resource of wilderness, and to strengthen our commitment to protecting these vital lands and waters now and for future generations.

Since 1976, when it became the fourth federal agency to be responsible for managing wilderness under the Wilderness Act, the Bureau of Land Management has played a unique role in wilderness preservation.

Numbering approximately 260, and encompassing a wide variety of environments, the nearly 10 million acres of BLM wilderness areas preserve ecosystems—deserts, grasslands, and prairie—which would otherwise be only a minor component of the National Wilderness Preservation System. Combined with the National Park Service, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and the U.S. Forest Service, the National Wilderness Preservation System includes more than 800 wilderness areas spanning more than 111 million acres.

Though millions of people visit wilderness areas annually, you are likely to find solitude in BLM areas where exploration and self-discovery are a hallmark experience.

In the Black Rock Desert Wilderness of Nevada, your mind will seek to fill the space of vistas and mirages pooled in the desert heat. Farther south, in Arizona, the Eagletail Mountain Wilderness offers views of rock strata, colors seeping throughout the mountains and complemented by arrangements of natural arches, spires, monoliths, and sawtooth ridges. In New Mexico, time has molded a fantasy landscape rich with fossils from dinosaurs, a place called the Bisti/De-Na-Zin Wilderness.

An unfiltered view of nature is not new. Designated wilderness areas, like the rest of the United States, are the current and ancestral homelands of Tribal Nations and Indigenous peoples, many of whom have deep cultural, historic, and spiritual connections to these places.

“We did not think of the great open plains, the beautiful rolling hills, and winding streams with tangled growth, as "wild."” wrote Chief Luther Standing Bear in his 1933 essay, Indian Wisdom. “To us it was tame. Earth was bountiful and we were surrounded with the blessings of the Great Mystery.”

Meanwhile, wild places have driven the plot of familiar stories the world over.

William Shakespeare, who is often praised for his love and understanding of nature, set a pastoral tone for the remainder of his Elizabethan crowd-pleaser As You Like It in Act II, Scene I, when Duke Senior, exiled to the cold, windy and rugged Forest of Arden, says to his followers:

And this our life, exempt from public haunt,

Finds tongues in trees, books in the running brooks,

Sermons in stones, and good in everything.

I would not change it.

All this speaks to Howard Zahniser's belief in the need for wilderness to exist so that people may achieve a true understanding of themselves, their culture, their own natures, and their place in nature. The certainty of Zahniser's belief is in his 1955 essay, The Need for Wilderness Areas, in which he links the prosperity of all life on Earth with the prosperity of humankind.

“This need is for areas of the earth within which we stand without our mechanisms that make us immediate masters over our environment—areas of wild nature in which we sense ourselves to be, what in fact I believe we are, dependant members of an interdependent community of living creatures that together derive their existence from the sun,” Zahniser wrote. One year later, he would write the first draft of the bill that became the Wilderness Act.

After nine years, 65 rewrites and 18 public hearings, the bill passed in August 1964. It was signed into law September 3 of that year. Howard Zahniser, a lover of nature and literature, champion of wilderness and wildness, had died months before, on May 5.

Zahniser’s son, Ed, has a revealing family story about his father, who grew up in northwestern Pennsylvania. In a tribute titled Preserving Wilderness and Wildness as Enlarging the Boundaries of the Community, the younger Zahniser says his father needed eyeglasses, but didn’t get them until far into childhood.

“With their aid he discovered that the world had sharper edges and even greater natural beauty than he had previously imagined,” Ed Zahniser writes. “A public school teacher introduced him to birdwatching and inspired a lifelong fascination that no doubt attracted him to his eventual work in conservation.”

With that, we encourage all Americans to discover and rediscover wilderness and other unfiltered natural places. Speaking without words, they are the prequel to the human stories that begin with once upon a time.

Related Stories

- BLM recreation sites available to all: Exploring accessibility on Arizona’s public lands

- Overcoming challenges to move the BLM forward: Nikki Haskett

- A day in the life of a BLM Hobbs Petroleum Engineering Technician

- BLM Recreation Sites Available to All: Exploring Accessibility on Alaska’s Public Lands

- A former boomtown’s second life as storyteller in New Mexico