You are viewing ARCHIVED content published online before January 20, 2025. Please note that this content is NOT UPDATED, and links may not work. Additionally, any previously issued diversity, equity, inclusion or gender-related guidance on this webpage should be considered rescinded. For current information, visit https://www.blm.gov/blog.

On our birthday, a land of plenty glows for all

Bureau of Land Management

By: Derrick Henry, BLM-Headquarters Public Affairs Specialist

Dawn kindled the jagged horizon, scooping purple and gold onto the landscape. Birdsong polished the air. Soon, the sky’s glittered cape vaporized to the thrill of a local resident who had waited for hours. A pleasant July morning on public land. Elsewhere, people woke and switched on appliances and checked their charged devices. Sunrise solitude, the thousands of people waking to reliable power—and many other things—were linked by the Bureau of Land Management’s 75-year stewardship of a land streaked with blessings.

Let’s roll back to another July morning, this time in 1946, Washington, D.C. The BLM has been established as a new federal agency. The workload includes managing a patchwork quilt of public lands using outmoded, and often conflicting, mandates of about 3,500 laws passed during the 150 previous years. The BLM leans in.

Over decades, the agency sheds its growing-pains and masters the ability to obtain the highest, sustainable benefit from one in every 10 acres of land in the United States, bringing in more money each year than its operational budget. To develop this proficiency, the BLM relies on experience reaching back to the early years after America’s independence, when the young nation began acquiring additional lands under the 1783 Treaty of Paris.

Under that treaty, which marked the end of the Revolutionary War, Great Britain relinquished its claim to the 13 colonies and ceded another 237 million acres of land reaching west to the Mississippi River, forming the nation’s original public domain. Congress at first used these additional lands to encourage homesteading and westward migration, bringing about the General Land Office, or GLO, in 1812.

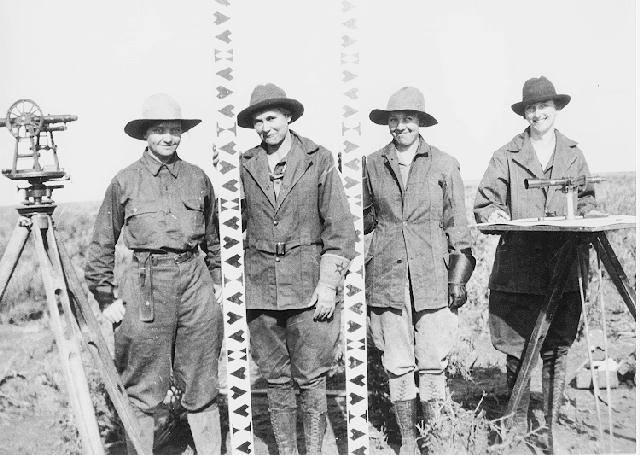

Over time, values and attitudes regarding public lands shifted, and Congress merged the GLO and another agency—the U.S. Grazing Service—creating the BLM in 1946. A tangle of responsibilities and bureaucratic adventure awaited the new agency.

In addition to the duties of the GLO and the Grazing Service, the BLM also incorporated the Alaska Fire Service, various revested lands (including the Oregon and California Railroad lands and the Coos Bay Wagon Road lands) and multiple mineral reserves. To top it off, there was no new mandate for the BLM, other than the authorities and functions of its predecessors: The GLO handled settlement, land sale, land exchange, and mineral entries in grazing districts, plus managing grazing lands outside grazing districts; the Grazing Service primarily handled grazing policy. Further, both agencies had been responsible for land classification and planning within grazing districts.

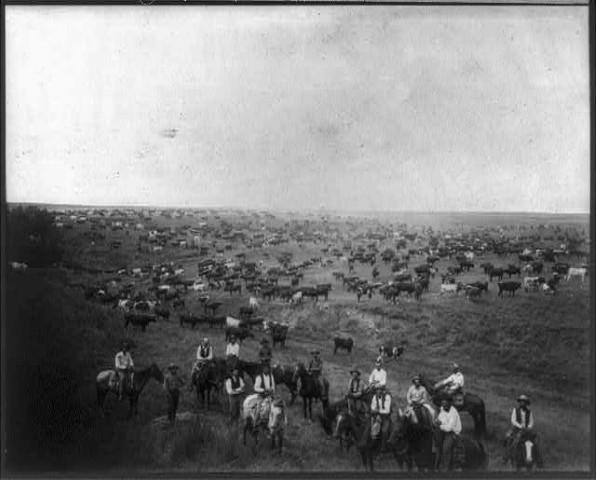

The BLM over several years reformulated its GLO and Grazing Service backgrounds, emerging with a fresh face. Reinvigorated, the agency established various professional programs covering forestry, recreation, minerals management, wild horses and burros, and wildlife. These programs anticipated that public land would be simultaneously used for two or more purposes, often by two or more persons or interests. This multiple-use approach also promoted President Theodore Roosevelt’s decades-earlier pronouncement that land and its resources had an inherent worth beyond extraction and development.

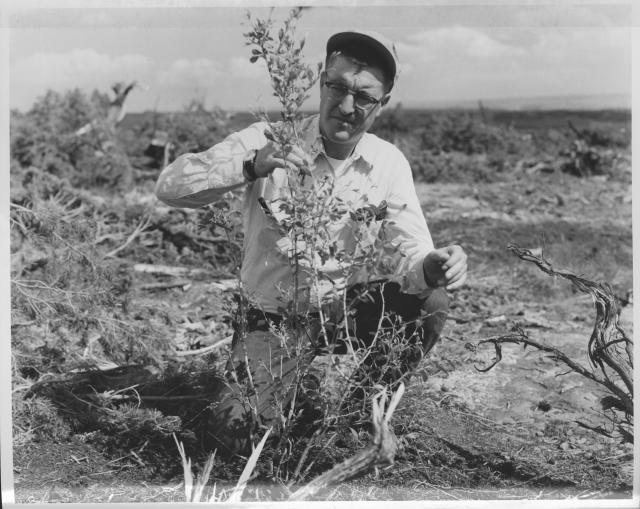

Later, the BLM began using the principle of balanced use to reconcile conflicts over how resources would be used at the same time on public land, as well as managing wild and scenic rivers and national scenic and historic trails. Over time, new environmental and conservation laws would change the BLM’s business practices. Chief among those laws was the Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976, which formally recognized the work the BLM had been doing all along and continues to do: managing public lands under the principles of multiple use and sustained yield.

Of all federal agencies, the BLM is the only one that manages so many activities in nearly every state with the expectation that this rich layer cake will be available for future generations.

Cattle graze on lands where wild horses roam, hunters pursue pronghorn, and artists draw inspiration. Elsewhere, enthusiasts ride, fish and hike among forests that provide timber for lumber and other products. In other places, power from solar and wind projects electrify transmission lines. Wildland firefighters wrangle dangerous wildfires with technology and muscle. Law enforcement officers help guide and protect recreating visitors. Below the surface are coal seams, copper, bentonite and other valuable minerals. Go deeper, and oil and gas platforms extract fluid minerals. Meanwhile, geothermal energy, the basis for geothermal electric power, radiates through the earth’s crust. At every level, there is an opportunity for valuable scientific and cultural knowledge to better manage these lands that provide everything from solitude, to electric power for thousands of homes, to knowledge used for space exploration.

The demand for these resources, spread across 245 million acres above ground and 700 million acres concealed below, never stops.

In response, the work that BLM employees do to meet this demand annually generates immense socioeconomic output. In Fiscal Year 2019, activities on public lands accounted for $111 billion in economic output and 498,000 jobs supported. This includes activities and jobs associated with energy development, recreation, grazing, timber, and non-energy minerals development.

For all the stewardship over this land, the agency doesn’t have an origin story that captures the imagination, just a merger called for under the Reorganization Plan No. 3 Act of 1946 and pair of bureaucratic starting points: July 16, 1946, establishment day; and December 10, 1946, enactment day. But this dry wording 75 years ago set in motion hard work by real people on the ground who turn public policy into reality. From the Arctic Ocean to the border with Mexico, and from Key West, Florida to the San Juan Islands of Washington State, this work creates a living anthology of our relationship with the public and public land.

It’s summer 2012, during the Trinity Ridge wildfire in Idaho. Helicopters churn the yellow air. During a public meeting at a local motel, fire information officers will stay for hours to answer everyone’s questions about the wildfire. A couple years later, on the South Fork American River in California, a cleanup crew heads to a popular rest area for whitewater rafters. A kayaker hails us and paddles over. He is with a nearby county and lends a hand. Members of a youth summer camp clap and cheer when our raft departs the rest area. In Wyoming months later at an oil field, an employee talks about mitigation strategies while a local reporter takes notes. In New Mexico, following a series of challenging tribal public meetings, a BLM employee says she will keep working to change the perception that the agency is simply checking off the box.

This work is threaded through with partnerships and consultation involving industry, academia, non-governmental organizations, communities, and State, Tribal, and local governments. At the heart of it all are BLM employees who understand the value of public involvement. While it is difficult to please everyone, we are happy to lift the hood to show people what we are doing. We do this with in-person meetings and consultation to mass-communications technology that enables us to reach more people in more places.

The result has been consistent long-term conservation, recreational and commercial benefit for the public good. Sometimes it’s through conservation projects to restore land and water—efforts craving public involvement. Sometimes it’s in the form of energy development, all kinds. And sometimes it’s a solitary witness, watching the value before her snap into view under the last shedding of night and its stars, a 3-D experience available nowhere else on Earth.

Our work continues as we try to get the upper hand on intersecting challenges, identified by the current administration, involving public health, racial equity, climate change, and economic rebuilding. We’re now managing vast resources while considering the effect of a stubborn virus 10,000 times smaller than the width of a human hair stuck to your work-at-home computer screen. On a larger scale, we are supporting the White House’s call for a once-in-a-generation opportunity to ensure that all communities—including under-represented communities—benefit from public lands decisions; that we acknowledge and manage for real effects of climate change; and that public lands generate fulfilling jobs.

Through history and across administrations and transitions, we have proven to be one of the taxpayers’ best investments. We remain well-suited to address fresh priorities, including those that enable us to reimagine our stewardship. And while our roots go back to the establishment of the GLO in 1812 and our heritage even farther back, our agency and its mission remain relevant as we lean again and again into future opportunities and challenges.

This year, we are celebrating our 75th year as an agency. That’s 75 candles, each standing for numerous decisions and actions backed by public outreach, partnerships and historical context. They make our workspace—the public lands—a well-lit place for stewardship. For our birthday, we extend to you an invitation, one that has stood for decades: join us as we honor, harvest and care for this natural wealth owned by us all.

Learn more about the Bureau of Land Management by visiting our website.

Want to see more amazing photos? We’ve got plenty on our flickr page!

Related Stories

- Protecting Lands and Communities: Shaila Pomaikai Catan

- Celebrating the power of public lands through tourism and community impact

- Top 5 things to know about the Comprehensive Animal Welfare Program

- First 100 days: BLM drives energy expansion and national strength

- BLM Recreation Sites Available to All: Exploring Accessibility on Colorado’s Public Lands